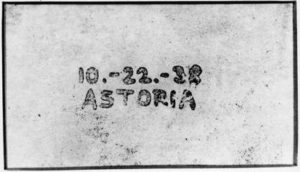

The first xerographic copy ever made, as created by Chester Carlson and his assistant.

Although Chester Carlson invented Xerography in 1938, it was twenty-one years later that the first office copier was available to the public. During the first eight months of production, Haloid (later renamed Xerox) sold more copiers then they expected to sell in the products entire life cycle.

Inventor: Chester F. Carlson

Chester F. Carlson photo courtesy University of Rochester

Criteria; First to invent. First to patent.

Birth: February 8, 1906 in Seattle, Washington

Death: September 19, 1968 in Rochester, New York

Nationality: American

Invention: Xerography

Definition: Forming an image by the action of light on a specially coated charged plate; the latent image is developed with powders that adhere only to electrically charged areas

Patent: 2,297,691 (US) issued October 6, 1942 for Electrophotography

Chester Carlson

The astounding success of xerography is all the more remarkable because it was given little hope of surviving its infancy. For years, it seemed to be an invention nobody wanted. To know why it eventually prevailed is to understand the mind of Chester Carlson. For xerography, and the man who invented it, were both the products of hardship and travail.

Chester Carlson was born in Seattle on February 8, 1906, the only child of an itinerant barber. The family settled in San Bernardino, Calif., and at the age of fourteen, Carlson was working after school and on weekends as the chief support of his family. His father was crippled with arthritis and his mother died of tuberculosis when he was seventeen.

Even as a boy, Carlson had the curious mind that always asked the how and why of things. He was fascinated with the graphic arts and with chemistry -- two disciplines he would eventually explore with remarkable result.

As a teenager he got a job working for a local printer, from whom he acquired, in return for his labor, a small printing press about to be discarded. He used the press to publish a little magazine for amateur chemists.

Upon graduating from high school, Carlson worked his way through a nearby junior college where he majored in chemistry. He then entered California Institute of Technology, and was graduated in two years with a degree in physics. More problems faced Carlson as he entered a job market shattered by the developing Depression. He applied to eighty-two firms, and received only two replies before landing a $35-a-week job as a research engineer at Bell Telephone Laboratories in New York City.

As the Depression deepened, he was laid off at Bell, worked briefly for a patent attorney, and then secured a position with the electronics firm of PR. Mallory & Co. While there, he studied law at night, earning a law degree from New York Law School. Carlson was eventually promoted to manager of Mallory's patent department.

"I had my job," he recalled, "but I didn't think I was getting ahead very fast. I was just living from hand to mouth, and I had just gotten married. It was kind of a struggle, so I thought the possibility of making an invention might kill two birds with one stone: It would be a chance to do the world some good and also a chance to do myself some good." As he worked at his job, Carlson noted that there never seemed to be enough carbon copies of patent specifications, and there seemed to be no quick or practical way of getting more. The choices were limited to sending for expensive photo copies, or having the documents retyped and then reread for errors. A thought occurred to him: Offices might benefit from a device that would accept a document and make copies of it in seconds. For many months Carlson spent his evenings at the New York Public Library reading all he could about imaging processes. He decided immediately not to research in the area of conventional photography, where light is an agent for chemical change, because that phenomenon was already being exhaustively explored in research labs of large corporations.

Obeying the inventor’s instinct to travel the uncharted course, Carlson turned to the little-known field of photoconductivity, specifically the findings of Hungarian physicist Paul Selenyi, who was experimenting with electrostatic images. He learned that when light strikes a photoconductive material, the electrical conductivity of that material is increased.

Soon, though, he began some rudimentary experiments, beginning first -- to his wife's aggravation -- in the kitchen of his apartment in Jackson Heights, Queens. It was here that Carlson unearthed the fundamental principles of what he called electrophotography --later to be named xerography -- and defined them in a patent application filed in September, 1938. "I knew," he said, "that I had a very big idea by the tail, but could I tame it?"

So he set out to reduce his theory to practice. Frustrated by a lack of time, and suffering from painful attacks of arthritis, Carlson decided to dip into his meager resources to pursue his research. He set up a small lab in nearby Astoria and hired an unemployed young physicist, a German refugee named Otto Kornei, to help with the lab work.

It was here, in a rented second-floor room above a bar, where xerography was invented. This is Carlson's account of that moment: "I went to the lab that day and Otto had a freshly-prepared sulfur coating on a zinc plate. We tried to see what we could do toward making a visible image.

Otto took a glass microscope slide and printed on it in India ink the notation '10-22-38 ASTORIA.'" We pulled down the shade to make the room as dark as possible, then he rubbed the sulfur surface vigorously with a handkerchief to apply an electrostatic charge, laid the slide on the surface and placed the combination under a bright incandescent lamp for a few seconds. The slide was then removed and lycopodium powder was sprinkled on the sulfur surface. By gently blowing on the surface, all the loose powder was removed and there was left on the surface a near-perfect duplicate in powder of the notation which had been printed on the glass slide.

"Both of us repeated the experiment several times to convince ourselves that it was true, then we made some permanent copies by transferring the powder images to wax paper and heating the sheets to melt the wax. Then we went out to lunch and to celebrate."

Fearful that others might be blazing the same trail as he -- which is not an uncommon occurrence in the history of scientific discovery -- Carlson carefully patented his ideas as he learned more about this new technology. His fear was unfounded. Carlson was quite alone in his work, and in his belief that xerography was of practical value to anyone. He pounded the pavement for years in a fruitless search for a company that would develop his invention into a useful product.

From 1939 to 1944, he was turned down by more than twenty companies. Even the National Inventors Council dismissed his work. "Some were indifferent," he recalled, "several expressed mild interest, and one or two were antagonistic. How difficult it was to convince anyone that my tiny plates and rough image held the key to a tremendous new industry. "The years went by without a serious nibble.. .I became discouraged and several times decided to drop the idea completely. But each time I returned to try again. I was thoroughly convinced that the invention was too promising to be dormant."

Finally, in 1944, Battelle Memorial Institute, a non-profit research organization, became interested, signed a royalty-sharing contract with Carlson, and began to develop the process. And in 1947, Battelle entered into an agreement with a small photo-paper company called Haloid (later to be known as Xerox), giving Haloid the right to develop a xerographic machine.

It was not until 1959, twenty-one years after Carlson invented xerography, that the first convenient office copier using xerography was unveiled. The 914 copier could make copies quickly at the touch of a button on plain paper. It was a phenomenal success. Today, xerography is a foundation stone of a gigantic worldwide copying industry, including Xerox and other corporations which make and market copiers and duplicators producing billions and billions of copies a year. And to Carlson, who had endured and struggled for so long, came fame, wealth and honor, all of which he accepted with a grace and modesty much in keeping with his shy and quiet personality.

Had he held onto it all, Carlson would have earned well over $150 million from his remarkable invention. But before he died he had given away some $100 million to various foundations and charities. During Carlson's last years he was given dozens of honors for his pioneering work, including the Inventor of the Year in 1964 and the Horatio Alger Award in 1966.

Credit: http://www.ideafinder.com/history/inventors/carlson.htm